Early Banking in Cranbrook, Kent |

|

There was only a handful of country banks in England before 1750, the earliest in Kent being Fector's of Dover, established in 1700. The major incentive for their establishment was the industrial revolution as money was needed for investment in commercial enterprises in the Midlands, Lancashire, the Northeast, etc, but the landowners, gentry and others, with money to invest, lived predominantly in rural areas. Consequently, country banks grew in significant numbers towards the end of the 18th C. In 1784, Bailey's Universal Directory recorded 119 banks outside London and a government survey revealed that there were 280 banks in 1793, the year of the outbreak of war with France. In spite of monetary restrictions, interest rates continued to rise, which encouraged the growth in the number of local banks. Consequently, by 1802, there were 398, more than three times the number twenty years before, and by October 1811, the total had risen to 741, with 83 new banks being opened in the preceding 12 months. Country banks offered ca.2.5 - 3% interest on deposits, the money then being invested in a partner London bank, earning an interest of 3.5 - 4%. In turn, the London banks invested in major industrial schemes so that money from rural areas with a surplus of savings was invested in the growing industrial towns where there was insufficient capital. (1) Cranbrook's First Bank Waddington was a hop factor and must have had considerable means, as in the late 1790s, he had set about buying up numerous hop gardens in the Worcester and Hereford area. He had tried to persuade farmers there to withhold their crops from the markets, and thus raise the price, as he claimed that hops were selling at well below their true value. As a result, he was brought to trial in 1800 for 'forestalling hops', ie attempting to fix their market price. He was found guilty, fined £500, and sentenced to one month's imprisonment (4). Perhaps it was his contacts amongst the hop-growers of the Weald which suggested Cranbrook as a likely place to set up a branch of his Rochester bank. The bank, like most country banks at that time, issued its own notes (although none has come to light so far) and Waddington intended that holders of the bank's notes would receive interest at 2.5% every January and July. The letter stated that "The Profits of Banking will be thus equitably divided with my Neighbours: An advantage, which no other Bank has ever offered." This indeed was an innovative idea, a sort of co-operative bank with a dividend for using the bank's paper money. The letter then went on to extol the country banking system, maintaining that the economies of Maidstone, Hastings and Rye had thrived as a result of having their own private banks, three in the case of Maidstone by that date. Waddington also pointed out how useful the banks were for the subscribers to the new canal project across the Weald; he was a subscriber towards the cost of the initial survey (5). Although the letter was addressed from Cranbrook, he was not a local man and it is likely that he stayed at one of the town's inns when negotiating with local hop farmers. He was also an ardent republican, actively campaigning for the government to make peace with Napoleon. Since banks relied very much on trust for people to deposit their savings, local farmers and businessmen in the Weald may have had some difficulty with his politics and it does not seem likely that the bank had a life of more than a year, or two at most. The building was owned by William Dadson, a "Grocer, Draper, and Cheesemonger of Goudhurst", who in December 1805 sold it along with his other properties in Goudhurst as he was planning to go "into the Hop Factoring Business, at the Talbot Buildings, Borough" (6). In this he was perhaps influenced by Waddington and it is interesting to note that (a relative?) James Dadson, a hopfactor of Southwark, purchased Bakers Cross Brewery and settled in Cranbrook in 1804 (see article in Cranbrook Journal no.7) The premises were again advertised for sale in June 1806 by a London auctioneer as follows: Lot 5: A valuable brick built dwelling house and premises in the centre of the market town of Cranbrook, late the bank of S.F.Waddington, well situated for trade in any line requiring roomy premises, commanding both the Streets and near the Church, and will form a comfortable residence for a private family. Another advertisement described its location as opposite the Market house (6). Messrs Chapman & Co - Cranbrook Bank

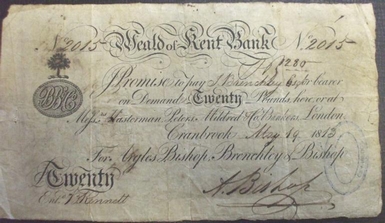

Watts, Buss & Co By law, the number of partners in a banking business was limited to six; they risked their entire property as security for their customers and if a bank failed, it was because the demands on the bank exceeded the assets of the partners, so that they were individually bankrupted. It was their property and standing in the community which effectively gave the public the feeling of security which they needed to entrust their funds to the bank. A Maidstone bank and a Chatham bank failed in 1805; in the latter case, the partners were taken to court for the houses and ships which they owned, in order to pay off the bank's debts (6). In spite of these potential risks, the first decade of the 19th century saw the greatest number of new banks being opened, including the Tenterden Bank in 1805 and the Ticehurst & Goudhurst Bank in 1807; the latter failed in 1815. For the next eight years, Watts, Buss & Co issued notes, first under the name "Cranbrook Bank", later the "Weald of Kent Bank". The notes carried a logo with the initials C&W, possibly denoting "Cranbrook and Weald" or could it be "Chapman & Watts"? Presumably the bank's business was expanding and more demands were being made on its capital so that John Wilmshurst soon joined the partnership. He was a cornfactor who lived at Osborne Lodge in Waterloo Road and owned two farms and several houses in the town, However, it seems likely that the individual business commitments of the partners meant they had little time to devote to banking and they decided to sell the business in 1813. On April 20th of that year, a notice appreared in the Maidstone Journal announcing that the banking concern had been relinquished "in favour of Messrs Argles Bishop, Brenchley & Bishop". It was also stated that "all our Notes, now in circulation, will be immediately paid off, on their being presented here, or at Messrs Weston's, Pinhorn & Co.'s in London." However, many bank notes remained in circulation and those which have survived show that certain partners had presumably by mutual agreement decided to underwrite certain denominations. Dr Watts was the signatory to the £10 notes and W.Buss the one pound notes. This may also have been a defence against forgery, as the wrong (forged) signature on a given denomination would be spotted by the bank clerk; the Tenterden Bank adopted a similar practice. Bishop & Co - Weald of Kent Bank

The Cranbrook bank was open on Saturday, September 10, 1814, but it was unable to meet all the cash demands made on it that day and it refused to make payments on the following Monday. The declaration of bankruptcy was on October 8th. The banking house was auctioned by the Maidstone auctioneers, Carter & Morris at the George Inn in Cranbrook on Sat 27th May 1815. It was described in the Maidstone Journal as: All that valuable Brick-built DWELLING HOUSE, with a GARDEN and an extensive Frontage, most eligibly situated within a short distance of the Market-Place, in Cranbrook, and lately used as a Banking House and Spirit Warehouse - Comprising two good rooms in front, which, at a trifling expense may be made a very excellent Shop, four bed chambers and three attics, kitchen, wash-house, and offices. For further Particulars, apply to Messrs. BURR and HOAR, Solicitors, Maidstone; or to the Auctioneers, Stone Street, Maidstone. Then followed two years when there is no evidence for any bank in Cranbrook - at least the rate books record that the earlier bank building was empty. By the beginning of 1816, Jeremiah Pethurst, the Cranbrook auctioneer, had bought the premises and probably rented it out short term. In April 1817. part of the premises was purchased by the owners of the Tenterden Bank. There were several partners; Cecil Pile's notes in Cranbrook museum say that the building was sold to Godden, Mace & Waterman of Tenterden, bankers, but no deeds have so far been found. In the ratebooks it was referred to as "Messrs Mace & Co". and the entry suggests that the new bank opened in part of the building, presumably using the same room(s) as the earlier bank. Mace & Co - Tenterden Bank

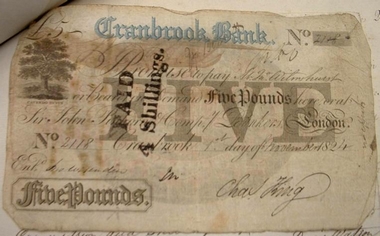

Charles King - Cranbrook Bank The words "Cranbrook Bank" on the top of the Notes are printed in Blue Ink, an Oak Tree is engraved on the left hand side of the Notes, and they bear date in August, 1823. It is particularly requested that the holders of the Old Notes will not circulate them, but immediately send them in for examination and exchange. Cranbrook Museum has some of these bank notes which, rather ironically, bore the Latin motto "Cavendo Tutus" meaning "Safety through Caution". They were all signed by Jno Wisenden, presumably King's bank clerk who recorded all the transactions in the bank ledger.

It does not speak well for King's business acumen that he took over the bank with no partners and very little property during a period of economic uncertainty. Perhaps not surprisingly, the next two years were disastrous for King; nationwide there was a general loss of confidence in banks, resulting in a major crash in 1825. The Cranbrook Bank (ie Charles King) was declared bankrupt in September 1825 (6) and commissioners were appointed to examine the bank's ledgers. The commisioners papers list around 250 creditors who registered their claims, some only having a few paper notes while others had four figure sums on deposit and hundreds of pounds in notes. The total money held on account was £10,618 2s 3d and there were further claims for notes in circulation to the value of £2,466. In addition, the local tradesman were owed £93 14s 1d for goods delivered but not yet paid for (10). This compares with just over £4,100 in debts incurred by the Cranbrook part of Bishop & Co's business when they went bankrupt in 1814. King's real estate was sold in lots by auction at 3 o'clock on Wednesday 14th June 1826 at the George Inn, Cranbrook. Advertisements in the Maidstone Journal described the High Street bank building as: A Messuage or tenement with the Yard, detached Washhouse, and newly erected Building, desirably situated in the Town of CRANBROOK, and late the residence of Mr Charles King, and used by him as a Banking-house. This is the present building now occupied by 'Quilters', the drycleaners in the High Street, and suggests that it may have been built by the Tenterden Bank or Charles King himself. With its canopy on fluted pillars, similar to the collonade in Hawkhurst, it was copying the fashionable architectural feature of the Pantiles in Tunbridge Wells. King also had a dwelling house described as: a newly erected MESSUAGE, being the northern house in Waterloo Place, pleasantly situated at the entrance of the Town of Cranbrook from Maidstone, comprising every requisite for the residence of a respectable family. Buss, Wilmshurst & Hague Under the new management, the bank continued uneventfully until the death of William Buss in 1832, after which the bank became Wilmshurst, Hague & Co for the ensuing decade. The Union Windmill and the Bakers Cross Brewery had also suffered economic problems in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars but the 1830s was a decade of strong business growth and the Bank continued to thrive. The story of local banking ends in 1843 when Wilmshurst, Hague & Co was taken over by the London & County Bank (a joint stock bank). By 1847-8, the bank had moved to the corner of Brewhouse Lane and was absorbed into the Westminster Bank in 1867. This merged with the National Provincial Bank in about 1970 to become the National Westminster or NatWest Bank which now occupies the site. References: Previously published by Tony Singleton in The Cranbrook Journal No.18 (2007) |

| Back to Home Page | |